Home Production: 1996-99

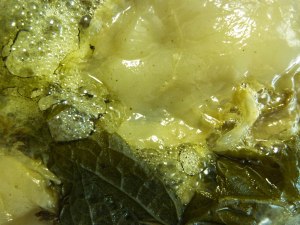

It's been a haul. In the beginning, we set up shop in our small ground floor apartment. There were years of nights spent up so late. So many nights when the baby wouldn’t go down, or stay down, and at two or three or more in the morning under the harsh light of florescence we'd be in our kitchen, with the babe in the backpack snoozing—or more likely not—and there would still be so much more clean up ahead and I would have to leave in a couple of hours to shelve catalog items for retail consumption at a Smith & Hawken garden store. I agree that normally we aren’t able to recall painful moments in too clear of detail as to save us from the trauma of having to relive the episode. Though I have to say, I remember the kitchen so well. The cupboards were this plaid of gray, red, and orange blocks with thin yellow stripes. The linoleum tiles of the kitchen floor were Etch-A-Sketch gray from centuries of traffic buildup. The kitchen was about 90 square feet. It housed the cabinets mentioned above, that only extended far enough along one wall to offer a single basin stainless sink. A sink which, it should be said, was placed into a countertop of yellow and brown leopard print Formica. It also contained a mustard-colored stove with a matching hood, of course. The refrigerator was white and modern, but lacked a water and crushed ice dispenser. We had a small white table from Scandinavian Designs with a hinged leaf, should we be expecting company, and four wooden chairs with rattan seats. It was also partial home to a huge industrial-grade stainless steel reach-in refrigerator, the rest of which extended into the entryway and blocked the front door from opening entirely. A 4' x 2' stainless steel Metro shelving unit sat in front of the kitchen's only window and supported, above the ground (in accordance with health codes floating in a sea of violations), five-gallon stoneware crocks filled with Brassicas in full ferment. There was another Metro shelf perched on the wall between the big fridge and a doorway. The doorway encompassed a step up to the living room which was floored with parquet and had a very, very low ceiling. The living room housed refrigerator number three. This one no longer functioned and was not plugged in. It was white and had a hole in its side where apparently a bullet had entered never to return. Under the bullet hole there were streaks of rust, looking like blood, running through the letters W S B which were rendered in fat blue marker ink in the style which everyone recognizes as the Gang Font. West Side Berkeley is an appropriately named outfit that contains some of the most ambitious taggers of all the local social clubs. Their initials are scribbled liberally across the town's nooks and crannies. Inside the fridge I had rigged up an incubator switch to a light bulb which kept the compartment within the perfect 30-degree variance of 74 to 104 degrees. We used it to incubate white sushi rice which had been inoculated with the mold spores of Aspergillus oryzae, for koji, which we then set free in a vat of salted soybean mash to make miso. We used it to inoculate soybeans themselves with Bacillus subtilis natto or Rhizopus oligosporus for natto and tempeh respectively. Next to the gangsta fridge was a wooden warehouse pallet which was average in size and on the ground supporting vessels full of fermentation. On the other side was the koji table, where the koji was processed once incubation was complete. There was so much controlled rot occurring that, with the nearly palpable energy of transformation, there seemed to always be a buzz, felt above the hum of the fridges and the drone of the florescent bulbs above. Felt even above the buzz of insufficient stereophonic that Bob Edwards' voice echoed out of, carried on the first broadcast out from D.C., earlier than most truck drivers would catch. We were mostly slumped over ourselves by this time in the evening. That is except, of course, for the sleepless young one. I wonder if the energy of the house, due to the alchemical atmosphere, caused the babe to be mostly awake unless in motion for the first two years of his life. Or perhaps it was us clanging around every night until the witching hour. So we would be there amongst all that in the kitchen and the boy would be on my back in the Tough Traveler pack. I recall feeling stunned, like in the headlights, with all of this around me. There I was sifting around in drifts of shredded cabbage on the linoleum, the light gleaming off the stainless all around, and it's later then I can feel, and I’m madly wiping at the deposits of crushed Cruciferae in the crevice of the fold down leaf of the white table. And you know what? NPR can be so disconcerting at this time, feeling like this, with Bob Edwards saying, “Good morning—NATO has launched air-strikes in Kosovo—I’m Bob Edwards and this is Morning Edition,” and then the music comes up, and B.J. Leiderman gives us a rise and shine.

-Kevin